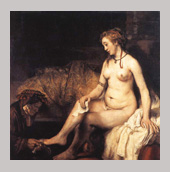

Bathsheba at her Bath / with King David's Letter

Rembrandt, 1654

photography, writing, fine art... stuff ... other stuff ...

Bathsheba at her Bath / with King David's Letter

Rembrandt, 1654

The story of Bathsheba plays a pivotal role in the life of David, whose kingship represents

the peak of Israel's fortunes in the Old Testament. Although Israel's political and economic

standing continues to grow under Solomon, David's son and successor, the seeds have already been

sown of the decay and eventual dissolution of the Davidic house, and with it the Kingdom of Israel.

David's adultery with Bathsheba heralds divisions within the royal family, leading to fratricide and

incest, then a disputed succession, and in due course the nation's split into two kingdoms. David,

whose covenant with God represents the culmination of the Abrahamic covenant, and who was the first

king to unite the southern kingdom of Judah with the northern kingdom of Israel, sows the seeds

(a metaphor consciously used by biblical authors) of the nation's dissolution and ultimate exile.

The story is this ... "it was the time of the year when kings go to war", but David, shirking his

duty, remains in the palace in Jerusalem. One evening he sees a woman, Bathsheba, bathing on a nearby

rooftop. He sends for her, she comes to the palace, they sleep together and she returns to her home. Then

news arrives at the palace; she is pregnant.

This is a problem. Bathsheba is married to Uriah the Hittite, who is away from Jerusalem fighting in

the king's wars. Uriah being a Hittite, his loyalty to David is one of choice, and in all likelihood he has

thrown away any prospect of returning to his own people. Uriah's loyalty has been betrayed. For Bathsheba,

she is in danger of being exposed as an adulteress, which is punishable by death.

That David was worthy to be king was established by his effectiveness as a shepherd defending the family's

sheep against wild animals. The motif of the shepherd king is prominent throughout the Old Testament, and Jesus

picks up the motif when calling himself the good shepherd in opposition to the Pharisees. One justification for

David's staying in Jerusalem is to defend the families of those who are away from home fighting on his behalf.

So not only is all this politically and socially embarrassing, it goes to the heart of his fitness to lead

the covenant people of God.

David's response is pragmatic. He recalls Uriah from the front and treats him to a banquet in the palace. At the

end of the evening, he suggests that Uriah go and enjoy a night in Bathsheba's bed.

But Uriah's principles intervene. 'It wouldn't be right. My comrades are away from home, in danger, and why should

I enjoy what they cannot'. He insists on sleeping in the palace.

When Uriah returns to the front, David sends with him a letter to his commander, saying that Uriah should be put

in the most dangerous part of the battle. He is, and is duly killed. The way is now free for David to marry

Bathsheba, and the child can be claimed as David's legitimate offspring. So it plays out.

Then Samuel, who years earlier had recognised the future king in the shepherd boy David, comes with a moral

about someone who takes the only sheep of a poor man rather than killing one of his own many sheep to feed to

a guest. David is furious, until he realises the point of the allegory. He repents, but too late to save the life

of the child, whom God causes to die as a punishment. The second child born to David and Bathsheba is Solomon.

What this account of the incident shows is that the initiative throughout rests with David. Important subsidiary

roles are played by Uriah and Samuel ... they both make decisions, and they both represent moral centres in contrast

to David's immoral or amoral behaviour. Bathsheba is little more than a cypher throughout. David sees her from a

distance, so he is attracted simply by her physical appearance. She features as little more than property ... the

disputed property of David and Uriah, but property nonetheless. Whether this is read as a blindness on the author's

part to Bathsheba's importance as a person in her own right, or as a subtle statement by the author of the political

and social realities of the day, is a matter of theological and textual judgement.

In that Rembrandt portrays Bathsheba life-size, however, and with David entirely absent from the image (at both these

points in departure from traditional representations of the story) it would appear that he favours the latter reading,

and addresses the silence of Bathsheba as the inevitable outworking of historic social and political realities.

Rembrandt shows her with King David's letter in her hand. The letter does not feature in the biblical narrative, and

logically, it could be a letter of initial invitation, or it could be a letter after the pregnancy has been discovered,

outlining David's response to the problem. The letter has traditionally been read as an invitation, however. It sits

in the image space as a simple fact; it is not being read by Bathsheba, it is barely being examined; it is not available

to the viewer of the image as a text, it is simply there as an object, as a symbol, in effect, of the king's authority.

It does not address Bathsheba as a person, the way a love letter might.

In screenplay, there is a simple formula; action = decision. That is to say, in a drama, action is not spectacle. Drama

derives not from explosions, fires, shootings, high-speed car chases ... it derives from the protagonist's having to

make a decision, and typically a decision which involves a high cost, where lives or moral principles are at stake. Rembrandt

has portrayed Bathsheba, then, at the moment of decision. Non-decision is not an option. No simple choice exists. Her

situation is impossible. That is to say, Rembrandt has made Bathsheba the protagonist in the drama.

There is a contrast, then, between the Bathsheba, and Rembrandt's Susanna surprised by the elders. For Susanna there are

similar issues at stake. Susanna takes the moral stand, and her life is indeed at risk. But in Rembrandt's picture

Susanna is simply a victim of the invasion of her privacy ... she clutches her robe to herself, and recoils from the

voyeuristic elders. There is nothing but instinctive reaction. Similarly, we can contrast the Bathsheba with Rembrandt's

painting of Hendrickje washing in a river, which has a certain similarity of mood to the Bathsheba, a quiet simplicity at

a moment of everyday ordinariness, an intimacy of portrayal ... a real woman with real flesh and sagginess but portrayed

with evident tenderness. But Hendrickje is facing no threat, has no decision to make. In dramatic terms, the Susanna and

the Hendrickje bathing are identical: there is no action. And clearly, although the Bathsheba functions at one level as a

loving portrait of (presumably) Rembrandt's mistress, Hendrickje, it is utterly unlike the majority of Rembrant's

portraits; only the later self-portraits can come close, with their 'dramatic' paint handling, and their portrayal of

a man who has faced (or is facing) difficulties ... Rembrandt's bankruptcy, the accusations of adultery which he and

Hendrickje (who lived together after the death of Rembrandt's wife Saskia) faced. Among the history paintings the one

which comes closest is the Samson, which functions as a portrait of Delilah, and which shows in the violence of Samson's

blinding the consequences both of Delilah's decision to betray him, and of his own decision to continue his affair with

her in spite of her earlier attempts to betray him. The only difference is that in the Bathsheba, the violence is all

offscreen. Which is to say that by this stage (1654, as against 1636 for the Samson) Rembrandt has learned how drama works.

He has abandoned spectacular colour effects to put the essential internality of decision out into the picture space.

For my own work, what this represents is a coincidence of the domestic and the agonistic, or, more precisely, the way

in which life constantly disrupts what should be domestic, peacable, and intimate. The agonistic shoves its way in, not

in a spectacular way but, in a surprisingly modern touch for our own bureaucratic age, by means of a piece of paper.

Such is the power of the two dimensional and the ephemeral.

Harry Smart, May 2003