photography, writing, fine art... stuff ... other stuff ...

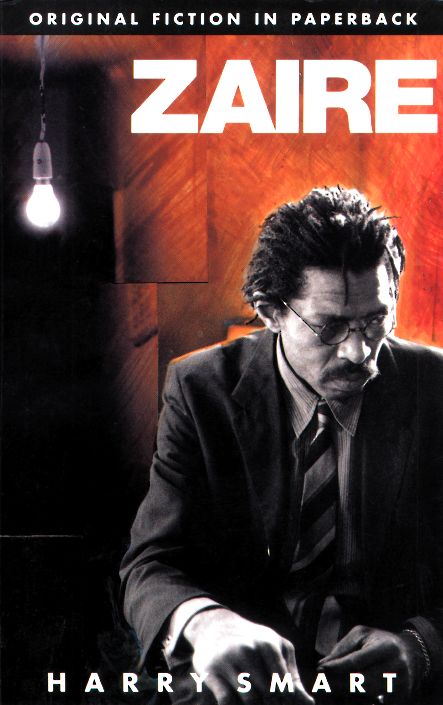

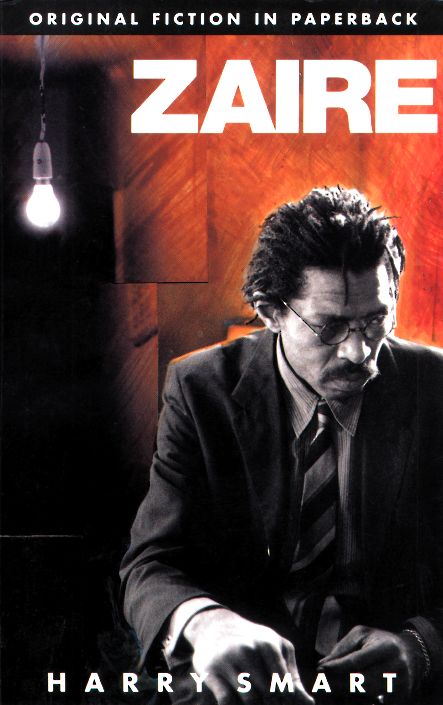

Zaire is a bizarre, emotionally intense and often horrific story. It leads the reader into the nightmare world of the deuxième cité, and to the abattoir, where the enemies of the state disappear.

Philippe is sent by his masters to London to do a job. The job has an awkward name: Lumumba. It is a name which takes us back to the Congo of 1960, a name which stands for all of Africa and the tragedy of a continent. In a world where idealism has no place, Philippe must negotiate some sort of peace with himself and throw the gears of the death machine into reverse.

An atmosphere of foreboding hovers over the narrative as Philippe plays a cat and mouse game with the Zairean Security Service. Miscalculation could lead to his death or that of his wife and small small son. The rules keep changing and Philippe is drawn into a chilling endgame.

In Philippe, Harry Smart has created an engaging black intellectual African hero, whose predicament and that of his country will stay in the mind of the reader long after the book is finished.

Thomas Manza stood at his bedroom window and looked out over the lights of Zürich as they sparkled in the darkness. A city at night; lights in offices and homes, streetlights, headlights, tail-lights. A universal. Manza looked and saw, it could be any city in the world, saw London and New York, saw the lights of Africa shining out like stars against the darkness, saw Brazzaville, Nairobi, saw Cairo and Kinshasa.

He turned away from the window and left the room.

He was sixty-three years old. When he left his country he'd been just over thirty, young for a cabinet minister, but everyone in that first government had been young. At thirty he'd been the oldest graduate in the Congo, one of only a handful of black men granted the privilege of studying in Europe.

The broad wooden stairway creaked beneath his feet as he made his way down in to the hall. His wife, hearing his footsteps, emerged from the sitting room. Beyond her, through the open doorway, Manza saw the TV. The sound was turned down low, subtitles spelling out a French translation of the German dialogue. After all these years, whispers, and the daily burden of translation.

'I have to finish my report for Etienne', he said. 'I promised I'd have it to him by tomorrow.'

'I'll bring you coffee, then?' asked his wife.

'Thank you', said Manza.

There was a sudden whirring in the hallway. The long-case clock was preparing to strike the hour. The whirring stopped and the first low chime shivered out through the house. Annette Manza shuffled off towards the kitchen. On the seventh stroke Thomas heard the door close softly behind her. He turned towards the study door. As the clock struck eleven he paused in the doorway, and stood for a moment. Stillness fell in the hallway, sudden after the striking hours, and the study too lay silent. He strode into the room, closing the door firmly behind him, and walked over to the desk. He flipped the power switch at the back of the PC and heard the fan and the hard disk whine up to their working speeds. The monitor bristled with high-tension charge. The clicks and whirrs of the boot sequence, of memory counts and initialisation, had become familiar and comforting. He switched on the laser printer, which added its own humming note. He walked round the desk and, with a sigh, settled himself into his chair. Behind him was the large, uncurtained window, and beyond its thick, double-glazed pane, the lights of Zürich.

*

The young African sitting in the passenger seat looked at his watch. The sea-green digital display changed silently to 11.00. Philippe Lukoji tapped lightly on the dashboard and the dark blue Renault moved forward. As it approached the high, metal gates they swung open and the car moved out into the dark street. It travelled quickly out of the city centre, onto Rämistrasse. No-one spoke.

They turned off to the right just before the Hospital, and soon the car was climbing up into Dolder, past big, solid houses which stood in generous grounds behind high walls and tall railings. The tree-lined streets were empty, the cars all settled down in off-road garages. Philippe spoke quietly to the driver, Alain, who pulled the car over to the kerb and stopped.

Alain was carrying a P-sieben while Robert, the gun-freak, had an early colt automatic, a 1911 he'd lovingly rebuilt. Philippe carried a Glock Model 17; Austrian-made, frame of hi-tech plastic, seventeen subsonic 9mm rounds in the magazine. Philippe held up his pistol and let them see him fixing the suppressor into place; they did the same. There was the sound of metal sliding on metal as Robert pulled back the slide on his colt, then the chunking sound as the spring threw it forward again, stripping a round from the top of the clip and loading it into the breech.

Philippe opened the door and stepped out into the street, looking for any sign of movement. Satisfied that there was no-one around, he ducked back briefly into the car.

'Los geht's', he said, and the two Swiss climbed out. They closed the car doors quietly and neither of them noticed that Philippe had left his pistol on the floor of the car. ...